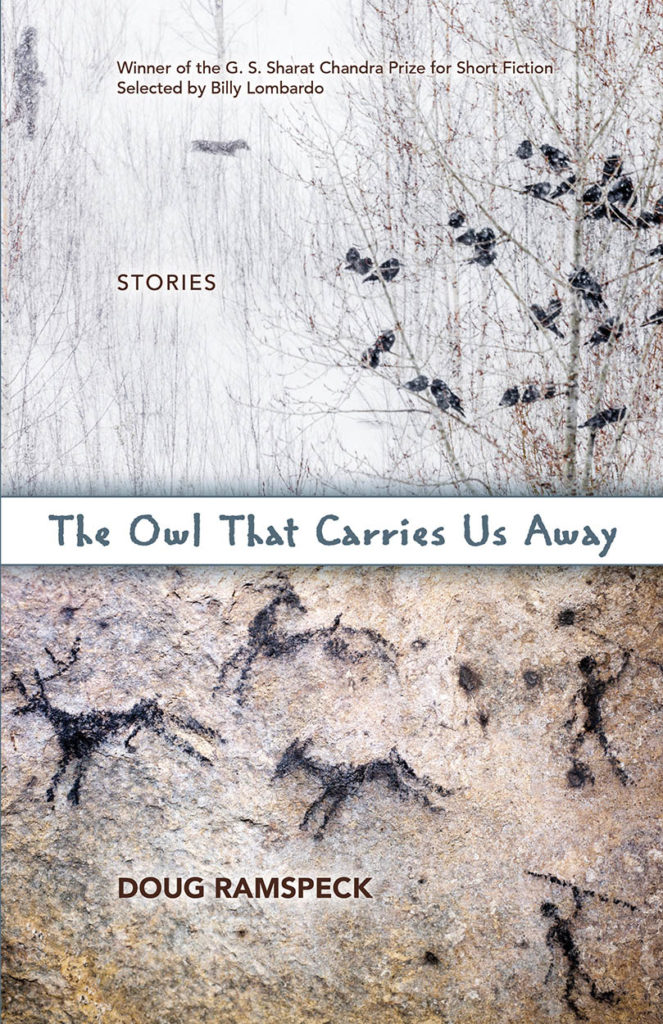

The Owl That Carries Us Away

Title: The Owl That Carries Us Away

Title: The Owl That Carries Us AwayPublished by: BkMk Press (University of Missouri-Kansas City)

Release Date: 2018

Genre: Short Stories

ISBN13: 978-1-943491-13-1

Buy the Book: BkMk Press, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound

Overview

In the title story of The Owl That Carries Us Away, the young protagonist finds a possum skull in his back yard, washes it with a hose, carries it into the house, and sleeps with it in his bed. Only later does the reader come to understand how the skull connects to a recent near-tragedy in the household. In other stories, a newly-married woman imagines that mushrooms are growing from her husband’s body, a funeral director is robbed by a teenage boy outside of an NFDA convention in Chicago, a woman with memory loss falls back in love with her abusive dead husband, a child comes to believe that his father is a bear, and a woman absconds with her sister’s baby and envisions a life for them in Florida. Winner G. S. Sharat Chandra Prize for Short Fiction. Bronze Winner Independent Publisher Award (IPPY).

Praise

“That Ramspeck is a prize-winning poet shows in this accomplished collection, winner of the G. S. Sharat Chandra Prize for Short Fiction: the language is grittily lyrical and each story in the moment. In one piece, the narrator says, ‘I see that my sons are wild creatures, feral boys in the backyard,’ and that beneath-the-surface sense of nasty brutishness surfaces throughout. A boy relentlessly pursued by a bullying older brother nearly drowns him, then wishes he had; ‘his brother will be lying in wait, will never forget this.’ A young woman is delighted with her new husband yet finds his presence, his very body, intrusive. And in the particularly affecting opening story, a boy who treasures a possum skull, a great sense of comfort to him with his father ill and his life lonely, is devastated when it’s destroyed by a would-be friend. Memory matters, too; a man finds his wife’s clothes ‘dangling their remembrance around him,’ while the father watching his sons is defined by the moment long ago when his brother drowned. VERDICT: Excellent reading for those who value meditative, beautiful storytelling.”

—Barbara Hoffert, Library Journal, starred review

“Ramspeck’s debut collection abounds with flawed families, tense confrontations, and unlikely moments of grace. In these stories, Ramspeck traces the emotional fallout from failed and imperfect connections. The threat of violence hangs over the proceedings: When recalling his first love, the narrator of ‘Slippery Creek’ recalls her disapproving father revealing his gun. ‘He almost smiled, as though he thought I might appreciate the gesture,’ the narrator notes—and that blend of implied violence and unexpected emotion serves as a template for much of what follows . . . These precise and resonant stories chronicle humble lives and unspoken traumas, making for a subtle and moving reading experience.”

—Kirkus Review

“Doug Ramspeck’s The Owl That Carries Us Away offers twenty-nine stories that deal with disappointments, childhood traumas, and tragedies, among other themes. The author presents his worlds in ways that often don’t outline the why’s in neat little bows. Instead, the stories present themes and ideas that demand their readers to feel the emotions. The Owl That Carries Us Away is a collection of stories that will leave no one unmoved.”

—Evgeniya Monico, New Pages

“What Ramspeck succeeds in here is to show us, in poignant, lyrical, but never fussy prose, what everyday fortitude looks like, what it’s like to look hardship straight in its eye and keep pressing on. These are flawed, sympathetic, fully human characters, and this is a sad, dark, terrific book.”

—Michael Griffith, author of Trophy and Bibliophilia

Excerpt from the story “The Owl That Carries Us Away”:

The boy is washing the possum skull with his mother’s hose on the stone steps. He found it in the mud beside the river. It was half-buried and stubborn, even when he poked it with a stick, even when he tried to pry it free with his fingers. Now he cleans the dirt out of the sockets with the spray of the hose. Pours the water through the teeth. Watches the water sliding across the pale bone. Hears the water splashing against the steps. The light snow that is falling is bone-colored, too, as though the great skeleton of sky has broken into shards and is coming down, falling out of the fat and low-slung clouds, and the boy carries the skull through the kitchen door, hiding it behind his back. Something is frying on the stove, lifting smoke, sizzling a complaint, but his mother isn’t there to tend to it. The room has been left by itself, the glasses and plates abandoned on the kitchen table. The boy hurries through the kitchen and up the narrow stairs with the skull. The stairway in the ancient house—built shortly after the Civil War—reminds him in its narrowness of the dark passage of a cave. He enters his bedroom and closes the door behind him. He lies on his bed and holds the skull on his chest. Strokes his hand across the hard, smooth bone. Feels for ridges and bumps and openings and crevices. Thinks of a cat purring beneath the rhythm of a palm. He pets the skull until he hears his mother calling out, and then he pushes it as far under the bed as he can reach, far back in the darkness.

“Wait here,” he says.